Augmentative and Alternative Communication and Cortical/Cerebral Visual Impairment (CVI)

Description

As an educator, the chances are, you've encountered a student with CVI and you may not have realized it. CVI is the number one cause of vision impairment for young children in developed countries yet it is considered to be underdiagnosed and undertreated. Many AAC tools rely on vision; therefore, educators must make special considerations when designing and introducing tools for students suspected of having visual impairments, including CVI.

Why Try Something New?

Educators often introduce AAC when they encounter a non-speaking student. Many of these AAC systems rely heavily on vision; therefore, it is essential that we adapt AAC tools to match a student's visual skills. If you have found yourself questioning your student's communication progress and/or their vision, we encourage you to continue reading. To learn more about CVI and visual skills, visit the Fundamentals of CVI Quick Win.

Finding the Balance of AAC and VI

A collaborative approach to AAC for students with CVI is essential for success. Teachers of the Visually Impaired (TVI) and Speech-Language Pathologists (SLP) should work together to plan, implement, and problem-solve AAC. Teachers, family members, and other school staff are also crucial to this process.

Finding the balance between a student’s visual and communication skills can be incredibly challenging, and often, the evidence-based approaches TVIs and SLPs use for vision and communication are at odds with each other. To develop vision, TVIs start with minimal pictures or real objects to build visual skills until the student can tolerate more. To develop communication, SLPs often begin with a more robust vocabulary, including many pictures or real objects. It’s essential to understand that both of these approaches are correct - and necessary - to build communication and vision in tandem. The key is finding the balance between the approaches that work best for each student individually - and create a communication system that is robust, but not visually taxing for a student.

In this video (7:00), you’ll hear a conversation between a TVI and an SLP answer the following questions:

- Where do you typically begin with a student?

- What do you want other professionals to know?

- How would you approach a student now, given your new understanding of roles?

Adapting AAC Tools

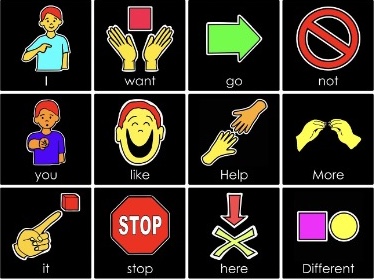

AAC tools and strategies for students with CVI will look different for each individual student, but they do share some commonalities. With this population, AAC should be:

- multimodal,

- adapted to their primary learning sense (also known as primary literacy media), and

- modified throughout the day based upon their visual fatigue.

Multimodal Communication

No one relies on one single mode of communication to get through their day. Many people use gestures, facial expressions, and vocalizations to support daily communication. Multimodal communication can also include signed languages, spoken languages, writing, and AAC! Any adult who works with a student needs to understand that they may communicate in a variety of ways and all communication attempts should be honored and responded to appropriately.

Watch this video (2:48) to see an example of a student and her sister using multimodal communication, including a Pragmatic Organization Dynamic Display (PODD) communication book, head shake/nod, and partner-assisted scanning in the store.

Adapted to their primary learning sense

One of the first steps in adapting AAC for students with CVI is to determine what main senses the student is using to interact with their environment. Through observation and trial and error, we can begin to determine if the student is using vision, hearing, or touch (or a combination of these) to make sense of the world around them. Examples of this can include:

- Vision/Visual: the student looks or brings objects close to their eyes

- Touch/Tactile: the student uses touch to explore objects

- Hearing/Auditory: the student responds when hearing voices or sounds

Once a team understands the way a student is interacting with their environment, they can begin to adapt AAC tools (and other educational materials) that best meet their sensory needs. For example, for a student who primarily uses their hearing/auditory sense, you might begin with partner assisted auditory scanning. Another student who primarily relies on their touch/tactile sense may do best to begin with whole or partial real objects.

For educational teams looking for a formal assessment, the Learning Media Assessment (LMA) can give information about what sensory systems a student is using to learn. A resource educational teams can utilize specifically for students with CVI is the Sensory Balance: An Approach to Learning Media Planning for Students with CVI.

Another way we can better understand how to adapt AAC is to understand a student’s visual behaviors, which are assessed by the TVI. The Visual Behaviors and AAC document, from the Perkins School for the Blind, matches a student’s visual behaviors with strategies and accommodations that may be helpful when introducing or adapting AAC.

Modified throughout the day

For students with CVI, one tool or mode of communication may not work throughout the day - you'll need to change tools, modes of communication, or how the student accesses their AAC multiple times a day to adapt to their visual needs.

AAC users with CVI may especially need to rely on alternative modes of communication when their vision is fatigued. It’s important for all adults who work with students with CVI to understand, introduce, and model multiple ways of accessing their AAC such as:

- When a student who uses an iPad with a communication app begins consistently closing their eyes during art class, an adult turns on the auditory scanning setting

- When a student who uses a high-contrast core vocabulary board begins consistently staring at a light in the room, an adult offers real objects as an alternative

It’s important that all adults who work closely with a student with CVI understand a student’s behaviors when they are visually fatigued, and how to adapt their access to communication.

What do we do if AAC isn't "working"?

While demonstrating AAC use, we are also building the student’s receptive vocabulary (the words they understand). We should continuously observe and problem-solve how, when, and why the student uses their AAC. It’s important to remember that learning to communicate using AAC takes time, much like how infants take time to speak their first words. As communication partners, we must consistently model AAC use throughout the day. We might sometimes rush the process or abandon the AAC tool too soon, so patience is crucial.

If the student uses AAC more in certain environments, consider factors like the setting, time of day, communication partners, activities, or visual fatigue. For students with CVI, a quiet, simple environment is often best, as distractions like light, movement, or noise can affect their ability to use their vision effectively. We encourage educational teams to consider the following as they engage in ongoing problem-solving:

- Colors: Are there colors that the student sees more clearly than others?

- Consult with your TVI to determine the colors that work best for the student (it's not always red and yellow) and incorporate those within the student's communication tools.

- Motion: Are visual distractions occurring in the environment?

- Position the student to minimize peripheral movement and reduce visual distractions from the environment.

- Visual Clutter: Does the environment have clutter, such as excessive pictures on the walls, decor, or shelves with a lot of materials?

- Create a clutter-free learning space with predictable locations for materials and ensure educators wear dark, plain clothing to minimize distractions.

- Background Noise: How much background noise is present in the environment?

- Reduce side conversations and background noise such as music. Consider using sound-absorbing materials like carpets and rugs to lower noise levels.

- Light: Do materials or devices have glare from overhead lighting or windows?

- Use matte finishes and backlighting to improve visual attention.

- Pictures versus Objects: Can the student visually access pictures or objects? For example, do they look at pictures in a book being read? Do they look at a tablet and interact with it?

- Real objects may be used for students who cannot visually access pictures yet.

- Spacing: Are communication symbols, pictures or objects too close together or too far apart?

- Work with your TVI to determine the optimal space between objects and/or pictures.

- Visual Fields: Are you presenting communication tools within the student’s field of vision?

- Collaborate with your TVI to find the best placement for the student’s AAC tools and ensure all communication partners understand how to present materials effectively.

These considerations are not comprehensive or exhaustive. Accommodations should be individualized based on a thorough assessment of the student. For more information on comprehensive assessments visit the Michigan Department of Education - Low Incidence Outreach website.

Potential examples of some of these (e.g. colors - green/blue colored core board; cluttered versus decluttered classroom; light - glare/matte laminating)

| Non-Example | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Example 1: |

|

|

| Example 2: |

|

Where can I learn more?

The following resources offer free, publicly accessible information and resources related to CVI

- Michigan Department of Education - Low Incidence Outreach provides consultation, training, and resources to Michigan families and educational teams.

- Perkins ELearning offers free video presentations to credit-earning online classes.

- Paths to Literacy offers foundational information and resources focused on literacy for children and youth with visual impairments.

- Pediatric Cortical Visual Impairment Society offers information and resources geared toward medical professionals, educators, and families.

- The Bridge School CVI Webinar Series offers short webinars on CVI and its impact on children who rely on AAC.

- AAC/CVI Matrix matches communication behaviors (from the Communication Matrix) with visual behaviors (from the CVI Range) and provides recommendations for AAC tools and strategies.

- 5 Essential Steps to Finding the Best AAC for a Learner with CVI

Guide to AAC Accommodations for People with CVI - offers tips for customizing AAC for individuals with CVI, based on research, to support effective implementation.